A team from the National University of Singapore (NUS) has developed a new conductive textile which enables wearable devices to interconnect and transmit data with far more strength than existing technologies.

The technology will help improve remote medical monitoring by healthcare professionals and family members.

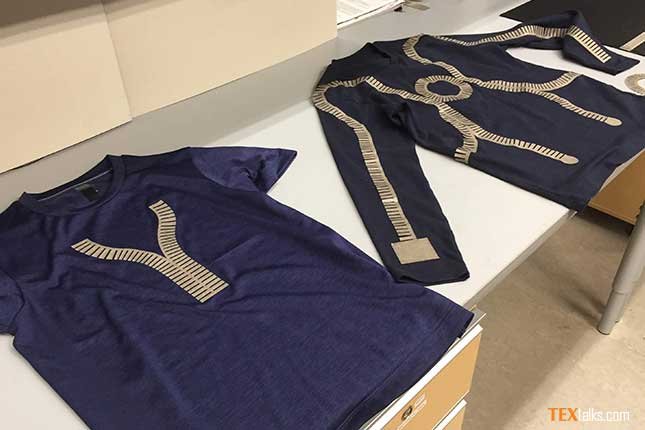

The material is based on comb-shaped strips of conductive fabrics using carbon, nickel, copper, gold, silver or titanium, attached with adhesives to the surface. The user wears non-textile sensors which are received by the material, which then collates and directing this information via novel conductive textile strips integrated into the garment to a separate internet-enabled device, such as a smart phone.

The device can then relay the information to external users, in what the team terms a ‘wireless body sensor network’. The conductive fabric corrals these data signals, confining them to just 10cm away from the body.

Until now, wearable devices using radio wave technology such as Bluetooth or Wi-Fi radiated signals in all directions, losing signal energy. The new system keeps signals close to the body, where it can be picked up by a smartphone. This also helps improve privacy and security.

Assistant Professor John Ho, who led the team, said the sensors worn on the body (like a smartwatch) or mounted on the skin (like a smart health patch) could use this conductive garment to communicate wirelessly between each other through radio-frequency signals, creating surface data waves across the body.

“Their proximity to the textile makes the connectivity 1,000 times stronger, which allows much longer battery life and can be even wirelessly charged by the hub or smartphone,” he says.

Ho said that the material could be produced in rolls and laser cut for use on garments at approximately US/metre.

He said that smart clothes incorporating these sensors could be folded, washed, ironed and the strips could even be cut without impacting the conductivity, and they were able to interact with any conventional wireless device.

The project had received an international patent and the team was now partnering with companies to commercialise it, with a view to having it on the market for consumers within five years, Ho said.